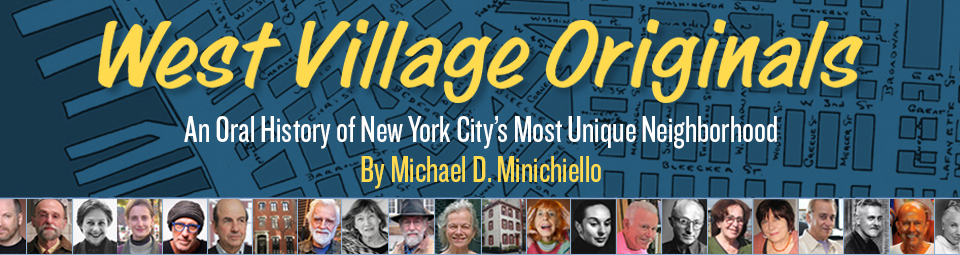

Architect James Stewart Polshek was born in Akron, Ohio in 1930. He designed the Clinton Presidential Library in Arkansas and Santa Fe Opera and, closer to home, the Rose Center for Space at the Museum of Natural History, Scandinavia House, the Lycée Français, and the new entryway to the Brooklyn Museum. “Build, Memory,” his look at a life in architecture, was published by The Monacelli Press recently.

Architect James Stewart Polshek was born in Akron, Ohio in 1930. He designed the Clinton Presidential Library in Arkansas and Santa Fe Opera and, closer to home, the Rose Center for Space at the Museum of Natural History, Scandinavia House, the Lycée Français, and the new entryway to the Brooklyn Museum. “Build, Memory,” his look at a life in architecture, was published by The Monacelli Press recently.

Architect James Stewart Polshek speaks fondly of growing up in Akron, Ohio. “My parents got along very well,” he says. “My mother was extremely orderly and she kept the house and our social life going. My father had this wonderful sense of humor and was beloved by everybody. He was very interested in politics and very sympathetic to Russia like a lot of progressive people at that time. I inherited a bit of both of them.” It would be his mother’s passion for order and his father’s fervor for social issues that would come to define his career.

Polshek had actually begun studying medicine when one day he saw a modern house going up in his neighborhood. “It was very radical and I thought that was wonderful,” he says. “As it began to go up I followed its progress, both inside and out. I soon started to build model houses at home. I stopped hanging around with my friends, let up on athletics even, and just built model houses. Eventually, I dropped pre-med and entered architecture school. One year later I transferred to Yale and got a graduate degree there.” What did his parents think of this decision? “They were puzzled at first and may have even been a little disappointed,” he says. “But not for long.” After apprenticeships with I.M. Pei and Ulrich Franzen and a Fulbright Scholarship to Denmark, Polshek received his first major project designing a research lab in Japan. He then returned to the United States, setting up his own firm in 1963.

If Polshek has a personal philosophy about architecture, it is his interest in buildings that serve the common good. “I feel that architecture has to have a broader definition,” he says. “This was reinforced by some of the teachers that I had and by my experience in Pei’s office. Very early on in my career I took on projects that encompassed historic preservation, non-profits, healthcare, and education; things that not every architect would jump at. Furthermore, I’ve always been more interested in doing additions to existing buildings. Both the Rose Center and the Brooklyn Museum are additions. I love adding something new to something old.”

While some architects would argue otherwise, Polshek also believes that architecture is not necessarily an art form and—to a large extent—buildings make themselves. “An architect is both constrained and encouraged by costs, building codes, the site, climate, the rules of the municipality, and the specific needs of the client,” he explains. “The actual ingredients are already there in the soup, but the architect puts in the seasoning. The style grows out of all those ingredients. This approach has always served me very well.” Then he laughs. “This isn’t something architects ordinarily give away, though!”

Polshek and his wife, Ellyn, moved to the Village in the early 1960s and, since 1973, have lived on Washington Square. “It was very different back then,” he says. “It was grungier but more hospitable to experimentation. In addition, the wealth that seeps out of every manhole cover and keyhole today was really absent. In 1973 our building was full of relatively young people with kids. Now apartments sell here for $3 or $4 million! It was that affordability that’s probably the single biggest difference from now.” At the end of the day, though, he admits that he couldn’t live anywhere else. “My wife and I have talked about it many times. But it makes us comfortable here.”

Polshek and his wife, Ellyn, moved to the Village in the early 1960s and, since 1973, have lived on Washington Square. “It was very different back then,” he says. “It was grungier but more hospitable to experimentation. In addition, the wealth that seeps out of every manhole cover and keyhole today was really absent. In 1973 our building was full of relatively young people with kids. Now apartments sell here for $3 or $4 million! It was that affordability that’s probably the single biggest difference from now.” At the end of the day, though, he admits that he couldn’t live anywhere else. “My wife and I have talked about it many times. But it makes us comfortable here.”

After a lifetime of viewing the Village through the eyes of both an architect and a humanist, Polshek is amply qualified to pinpoint his affection for it. “It’s really summed up for me in one word: scale,” he says. “By that I mean the relationship of the buildings to the human body and the amount of detail that you can feel, touch, and absorb visually here. It’s not absolutely unique because there are historic neighborhoods in other parts of the City. But as far as Manhattan is concerned, Greenwich Village is the home run.”

Photo: Maggie Berkvist