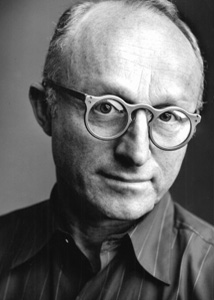

Long Island-born photographer Jan Staller has been in New York City since 1976 and a homeowner on Charles Street since 1993. In addition to numerous editorial assignments, solo shows, and group shows, he has had two monographs of his enigmatic photographs published: “Frontier New York” and “On Planet Earth.” His work is in the collections of numerous public and private institutions.

Long Island-born photographer Jan Staller has been in New York City since 1976 and a homeowner on Charles Street since 1993. In addition to numerous editorial assignments, solo shows, and group shows, he has had two monographs of his enigmatic photographs published: “Frontier New York” and “On Planet Earth.” His work is in the collections of numerous public and private institutions.

When photographer Jan Staller first moved to New York in 1976, it was his living arrangements that ultimately influenced his photography.

“I lived in a very dark loft with no direct light on Walker Street,” he recalls. “As a result, I was drawn to the river for a sense of nature. I would end up on the abandoned West Side Highway and it was a great refuge. When they started to demolish it I thought maybe I better take some photographs. In a way, that was my pursuit of nature along the Hudson. Actually, it is nature. It’s the river, and sunlight, and the horizon. It’s not the experience you get anywhere else but at the fringe of the city.”

“My early photographs were made at twilight,” he continues. “That was for two reasons. One was that I would always go out at the end of the day because I just wanted to enjoy the last hour of daylight and the sunset. Then I found myself staying out later and later and watching the street lights come on. This twilight effect was very dramatic because as the lights came on and the sky drew darker the street would become brighter. It was a cinematic quality almost like stage lighting and it was wonderful. I was able to take some very mysterious and ethereal photographs.”

Many of these photographs of the West Side Highway ended up in a monograph entitled “Frontier New York”, published by Hudson Hills Press in 1988. These images represented what Staller likes best about photography. “It’s the sense of discovery,” he says. He goes on to explain that one of the first things people did with photography was to bring back images of Pompei or ancient Greek ruins or faraway lands. They went exploring. “When I began to work,” he continues, “there was this question I posed to myself: Could I ‘explore’ the world without going anywhere and just work close to home? So I did, and it was a kind of discovery. To visit a location once or twice gives you the lay of the land. But to visit it again and again—as I did with the West Side Highway—is very valuable. In the hands and mind and eye of a practitioner, photographs can show us something different from what we might perceive if we were there ourselves. I wanted others to be able to see the place as I saw it.”

As a resident of Charles Street for two decades, what changes has he seen in the West Village? “Well, it’s become much more dense with high rises,” he says. “And there’s actually more noise in the neighborhood because the old brick buildings that blocked the sound from the highway were torn down in 2000 for the Maier towers. But I certainly am impressed with the personalities that have moved into the neighborhood. I have some very distinguished neighbors and I’m sure a lot of them got here through their hard work.” Could Staller imagine living anywhere else now? “Oh, no,” he says. “It’s my penultimate resting place. It’s not about the exploration and mystery that it had in the 1970s when it was still dingy piers blocking the river, but it’s a wonderful resource now just to appreciate on an aesthetic basis.”

Staller returns to talking about his early years exploring the West Side Highway.“This was a part of the derelict New York which kind of reverted back to a frontier,” he observes. “Because of that, one could experience the same kind of feelings that one could get in the woods: solitude and peace. That was a quality I enjoyed for quite a while until they tore it all down. Of course the river and the light are still there, but the experience is very different. I certainly wouldn’t claim any part of New York for myself, but I definitely enjoyed it for the few years that it was there. Walking up there on a snowy day, my footprints would be the only ones. That you could find this kind of peace in a city of eight million was sort of remarkable.”

Staller returns to talking about his early years exploring the West Side Highway.“This was a part of the derelict New York which kind of reverted back to a frontier,” he observes. “Because of that, one could experience the same kind of feelings that one could get in the woods: solitude and peace. That was a quality I enjoyed for quite a while until they tore it all down. Of course the river and the light are still there, but the experience is very different. I certainly wouldn’t claim any part of New York for myself, but I definitely enjoyed it for the few years that it was there. Walking up there on a snowy day, my footprints would be the only ones. That you could find this kind of peace in a city of eight million was sort of remarkable.”

Photo: Mark Seliger