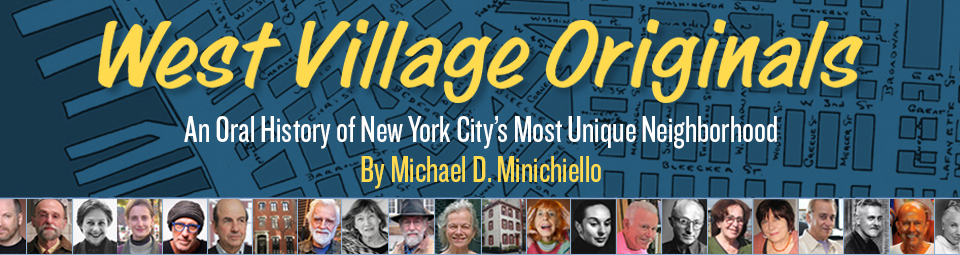

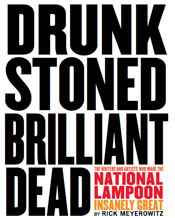

Illustrator, photographer, and writer Rick Meyerowitz was born in the Bronx in 1943. He spent twenty years with the National Lampoon as one of its most prolific contributors of illustrated articles. Abrams recently published his illustrated history of the magazine titled “DRUNK STONED BRILLIANT DEAD: The Writers and Artists Who Made the National Lampoon So Insanely Great.”

Illustrator, photographer, and writer Rick Meyerowitz was born in the Bronx in 1943. He spent twenty years with the National Lampoon as one of its most prolific contributors of illustrated articles. Abrams recently published his illustrated history of the magazine titled “DRUNK STONED BRILLIANT DEAD: The Writers and Artists Who Made the National Lampoon So Insanely Great.”

For illustrator Rick Meyerowitz, early influences were not comic books as one might expect, but rather the notion of art itself. “My mother always took us to museums and exposed us to fine art,” he recalls. “From my father, I got a love of drawing. While my influences were the great cartoonists and illustrators of my youth like N. C. Wyeth, Bill Mauldin, and David Low in England, I was also a great fan very early on of Jackson Pollack. I thought Willem de Kooning was the coolest stuff. I wanted to be an artist, but one who illustrated stories. So it wasn’t comic books that influenced me so much as the idea that drawing pictures was something I could do which would give me pleasure.”

After earning his degree from Boston University’s School of the Arts, Meyerowtiz returned to New York to begin his career as an illustrator. It was while delivering one of his illustrations to a client that his association with the National Lampoon began. “I ran into a writer named Michael O’Donoghue,” he recalls. “He was a great, amazing, funny guy and we became friends. In September of 1969 he called me and said he would like me to meet a couple of guys from Harvard who were about to start a national humor magazine. We were introduced and I came on board to work with the Lampoon six months before they published their first issue. I like to say I’m an ‘Original Lampooner.’ I really was present at the birth.”

As Meyerowtiz explains it, everyone was offended by the Lampoon’s stick-in-your-eye style of humor. “The counter-culture thought that the magazine was on their side,” he says. “They asked, ‘How could you attack Joan Baez or Bob Dylan? We thought you were with us!’ But we weren’t on anybody’s side. As far as we were concerned, they were as pathetic a target as the Nixon administration or Pat Boone. For myself, I wasn’t interested in offending anybody. I was just against hypocrisy and deadly dullness. To me, the lunatic actions of the Left were as crazy as the lunatic actions of the Right.”

“Although I had a huge impact on the look of the Lampoon for all those years,” he continues, “I also had another life.” This included raising two children, living on Jane Street for many years and then moving to Charles Street where he still resides. “All the while that was going on,” he says, “I was illustrating about 2000 ads for advertising agencies and articles for other magazines. The Lampoon was just a small part of my income and a small part of my production.”

When Meyerowitz and his family moved here in early 1977, “It was really great,” he remembers. “I would play stickball with my son on Greenwich Street and a car would come by every twenty minutes. The streets were that empty. Ours was one of the first conversions of an industrial building and that was pretty extraordinary at the time.”

While he is bemused by the significant changes to the West Village since, Meyerowtiz is not a fan of preserving it in amber, either. “I don’t think the area should be locked in time or stay exactly the same,” he admits. “While I love the historic and low-rise character of this neighborhood, I am somewhat tired of derivative red-brick buildings being built to look like something old. I believe you can retain the character of this neighborhood and still have some interesting and forward-looking architecture.”

While he is bemused by the significant changes to the West Village since, Meyerowtiz is not a fan of preserving it in amber, either. “I don’t think the area should be locked in time or stay exactly the same,” he admits. “While I love the historic and low-rise character of this neighborhood, I am somewhat tired of derivative red-brick buildings being built to look like something old. I believe you can retain the character of this neighborhood and still have some interesting and forward-looking architecture.”

What never changes for Meyerowitz, though, is his sense of having found a home in the West Village. “What I love is the light and the air and how I feel when I return from being uptown,” he says. “There’s a sense of relief to be in the quiet, sunny streets. It’s a small town thing and it always gives me a sense of homecoming. I know these streets very well. I’m often amused when I see people on all four corners studying maps, trying to figure out where the hell they are. The question is, do I help any of them or just smile and go home?” Then he says, laughing, “Because I know where I am and they don’t!”

Photo: Elizabeth Beautyman